Academic pharmacist Nataly Martini highlights the importance of understanding non-Hodgkin lymphoma and pharmacists’ roles in managing this condition

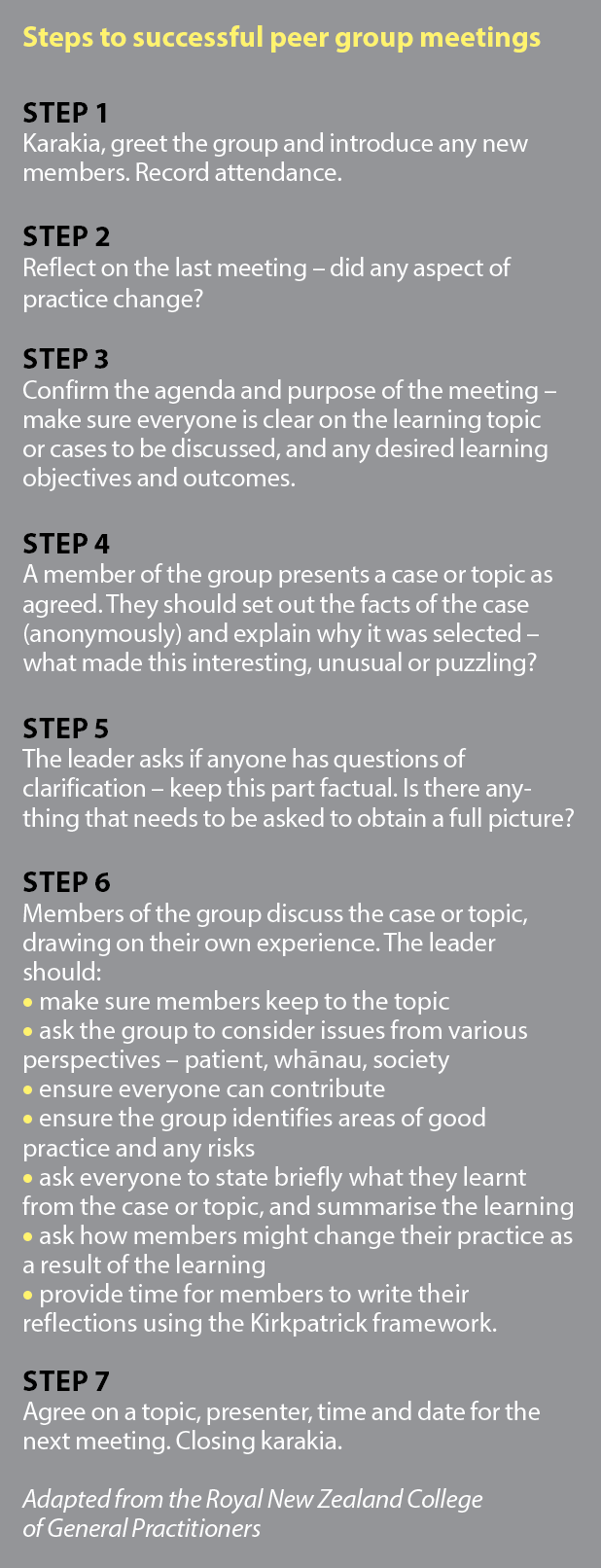

A guide to peer group meetings

A guide to peer group meetings

We are on our summer break and the editorial office is closed until 17 January. In the meantime, please enjoy our Summer Hiatus series, an eclectic mix from our news and clinical archives and articles from The Conversation throughout the year

The Pharmacy Council’s new recertification framework for practising pharmacists requires peer engagement in groups as an activity to maintain competence. Here, GP Jo Scott-Jones shares advice on running a successful peer group

On 1 April 2021, significant changes to the Pharmacy Council’s professional development requirements were implemented. This includes the requirement for “pharmacists to join or start a group of at least four professional peers that meets at least twice a year to support each other professionally and share learnings from successes, mistakes, innovations, case studies and published research”.

Note that only one meeting is required by the Pharmacy Council for the first year of the new recertification requirements (2021/2022).

It’s always annoying to be told you must do something, but once you get over that first hump, a peer group can be a great experience. Like most things, the more you put in, the more you can take out.

Peer review has been a compulsory part of general practice professional requirements for over 10 years, and most GPs, when asked, will describe both personal and educational benefits flowing from involvement with peer groups. This is especially true when the group forms a trusting environment where people can be honest and transparent with each other.

Peer groups provide educational value by offering an opportunity:

- to identify and understand personal learning needs, trends and patterns of practice

- for social learning and sharing of experiences

- for self-reflection and to explore variability of practice

- to assess where an individual sits within a range of expected practice.

Peer groups provide pastoral value by creating:

- a space for collegial support that enhances self-care

- an opportunity to reduce professional isolation inherent in day-to-day practice

- a community of practice.

Comparing actual practice with what can be defined as “best practice” in a structured, supportive environment has been shown to be an effective way of improving outcomes, especially when the process involves a small group coming from the same discipline.1

Peer groups have a lot of autonomy. They can be structured around an educational component by reviewing a new guideline or interesting research paper. As confidence grows, they may focus on aspects of clinical behaviour, review note-keeping or reflect on a recorded patient consultation. When fully mature, many groups spend more time considering the emotional impact of the work and provide direct support to members who are struggling with significant events.

The key to a great peer group experience is to develop a culture in which people can share vulnerability around their levels of knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. This level of trust within a small group requires an express intent and time to develop. So, where do you start?

You need to find a minimum of four people who agree to meet at least twice during the year for professional development and recertification purposes.

You may already have a social or professional network that you could form into a group. It does not have to be all pharmacists, although having a single profession in the mix does bring added benefits as the challenges faced are all the same.

If you are struggling to link with other pharmacists, talk to the health professionals you interact with most often – GPs, practice nurses, district nurses and social workers. The benefits to your community from building good relationships between the health team members is incalculable.

When fully mature, many groups spend more time considering the emotional impact of the work

Another option to consider is asking a GP if their peer group could include you. Although some groups have been stable for many years and have built a level of trust that can be disrupted by new people, if the group can flex, it’s easier to slot into a well-established process than have to create something new from scratch.

Remember, the group does not have

to meet in person. Many peer groups only meet through videoconference, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you are setting up a new group, at the first meeting, you need to agree on the purpose, process and rules of engagement of the group. Without doing this explicitly, the group is likely to falter at its first hurdle. An agenda is suggested below.

Karakia, welcome, whanaungatanga (20 minutes)

Be mindful of the cultural norms and needs of all members.

A karakia or prayer to open and close each meeting is an important step to ensure correct tikanga is followed. Ask if anyone would like to start the meeting with a karakia. If no one steps forward, consider saying the following:

“We all have a different understanding of what connects us as people, how we fit into the world, and what many describe as the spiritual aspects of our existence. At the start of the meeting, it’s good to stop for a moment, ground ourselves and be present.

“In the tradition of the tangata whenua, let’s start the meeting with a karakia.”

Tūtawa mai i runga

Tūtawa mai i raro

Tūtawa mai i waho

Tūtawa mai i roto

Kia tau ai te mauri tū,

te mauri ora ki te katoa

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e!

-

I summon from above

I summon from below

I summon from within

And from the surrounding environment

The universal vitality and energy to infuse and enrich all present

Unified, connected and blessed.

Then, welcome the group and ask people to introduce themselves. Whanaungatanga is the process of “getting to know you”.

If people already know each other, it can still be useful to do a round of introductions so that everyone has said something at the start of the meeting. You could ask everyone to introduce themselves and say what drew them to pharmacy, what they hope to get out of the meeting over the next 90 minutes, and what they enjoy doing outside of work.

If the group is quite large, it can be good to have people spend a few minutes talking to the person next to them, and then to introduce their neighbour to the group.

Why are we meeting? (20 minutes)

The Pharmacy Council believes that professional connectedness helps prevent competence diminishing over time. A peer group can enhance professionalism through the structured relationship with others who collaboratively, creatively, interactively and critically improve pharmacy practice.

Being clear about why the group exists is important

The group will not survive if it does not have a clearly defined reason for being. At the first meeting (or before, if you are well organised), ask members to independently scan the following list and to delete, add and prioritise group objectives:

- share information, knowledge, feedback and experience

- build awareness around social and cultural positioning

- seek knowledge about innovations, products, processes and regulations

- seek self-knowledge about assumptions and biases

- understand reactions through sensitivity to difference

- develop tactics to improve practice

- problem-solve issues related to practice

- build relationships with peers and community

- generate support within and between regions

- improve cultural safety and informed practice to benefit Māori hauora

- keep an open mindset for change in behaviours

- make decisions

- identify problems or opportunities

- limit risk.

Spend enough time as it takes to agree, as a group, on what the most important objective is for you all.

Being clear about why the group exists is important. If you go back to this at the start of each meeting, the group will stay focused and reduce wasted time.

If you are the group leader, be prepared to call out cynicism. “This group exists to meet the Pharmacy Council requirements,” is not a good start to a pleasurable experience.

Lay ground rules (20 minutes)

Ask the group what they think the rules of engagement are for them to be able to fulfil the group’s purpose. Common ground rules for peer groups include:

- punctuality

- confidentiality – what is said in the group, stays in the group

- everyone contributes

- always have an agenda

- avoid interruptions from outside

- avoid interrupting others

- promote focus on issues

- time keep – allocate extra time for off-topic chat

- park questions for later, especially if they are not strictly relevant

- query critically around a problem, not a person

- be mindful of how often you speak relative to others

- ask why and for clarification

- listen reflectively and actively

- always keep the dialogue and comments positive – avoid “no”

- explore differences, rather than avoid them.

Your group may come up with a different list. The key thing is to be explicit and for everyone to agree. Group trust will form more quickly if everyone follows the rules.

It’s important that clinical discussions are kept confidential. When discussing patient stories, avoid using names and identifiers. Consider, “Mr T, a 58-year-old Māori engineer with two children,” as opposed to, “Barbara who works at the bakers, the one with the mole on her nose.”

Agree on process and roles (10 minutes)

The group needs to agree to a structure for future meetings. When, where and how will the group meet? How long will meetings last?

The Pharmacy Council will only require two meetings a year – is this enough for the group to really be useful?

Meetings will be more efficient if there is a defined leader, a person identified to keep notes (scribe), and a timekeeper. These roles can be set at the start of each meeting or be shared around every year.

If the group is large enough, it is also helpful to have one person in each meeting allocated as researcher. During the meeting, they can be online exploring evidence and resources behind subjects that are discussed. This person is given permission to interrupt discussion and correct misconceptions if they arise. They can share the helpful information they find with the scribe, who can add it to the meeting notes.

Discuss group dynamics (10 minutes)

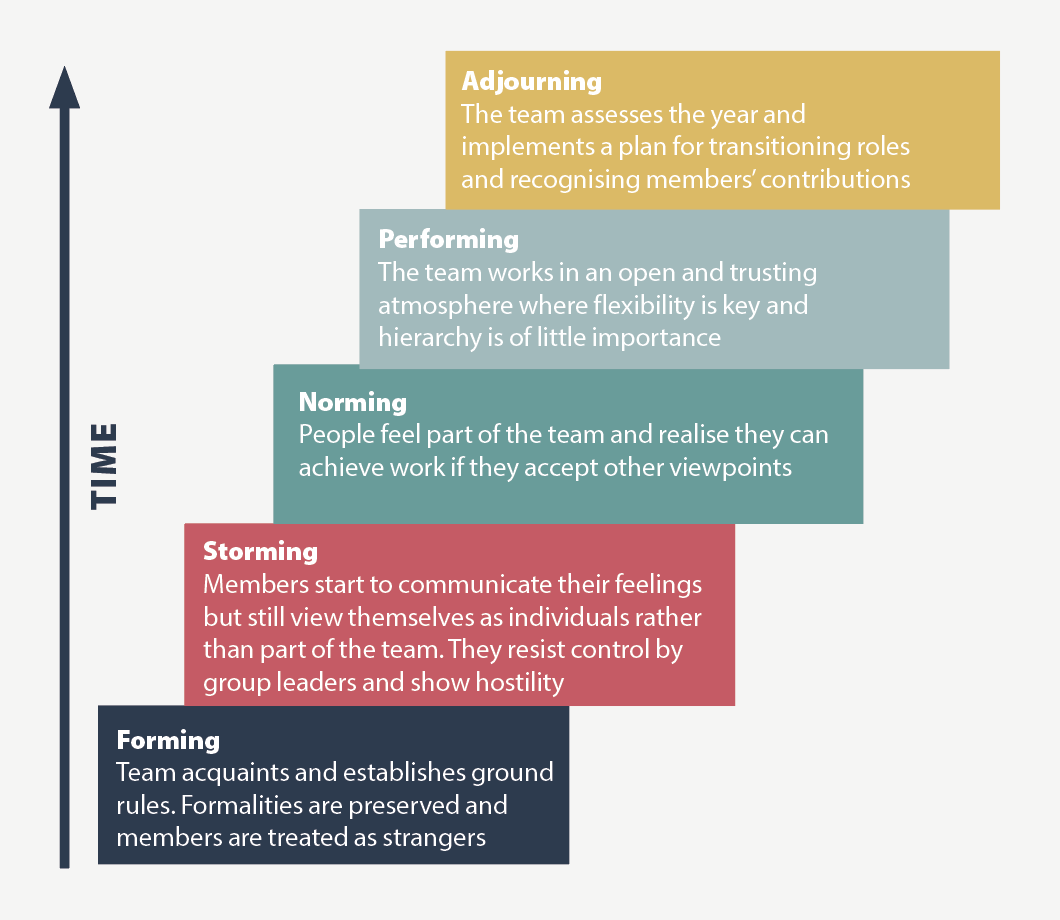

Share Bruce Tuckman’s stages of small-group development for an overview of the typical process (Figure 1).2

It is uncomfortable to discuss group dynamics. However, it is important to be explicit and acknowledge that some topics of discussion may be sensitive and challenge an individual’s values and morals, particularly with respect to cultural safety, racism and critical incidents.

Together, your group will share insights, knowledge and trust to move forward on a journey that is both intellectual and emotional.

- Ask the group to keep the following in mind during discussions:

- Who is likely to feel comfortable/uncomfortable?

- What are the power dynamics?

- What emotions are associated with critical incidents?

- Is everyone able/willing to contribute to this group?

The leader of the group has a special task in keeping everyone on track and ensuring the rules are adhered to. They should identify if anyone is being quiet and encourage them to contribute.

They need to look out for criticism and personal comments, and call them out, reminding people to be respectful and constructive.

They need to direct the conversation so that people get maximum value from the topic. This may involve asking people to step into one another’s shoes, to try to explore different perspectives and attitudes.

Close the meeting (10 minutes)

Agree on the next meeting date, time, leader and agenda (see panel). Setting the topic may be as simple as focusing on a requirement from the Pharmacy Council’s new recertification framework:

Keeping up to date – this could be based on articles published in Pharmacy Today.

Towards culturally safe practice – share what went well and what could be improved.

Critical incident – discuss any significant events or near misses; this could be based on your reflective account.

If you start with a karakia, it is important to end with a karakia. Again, ask if anyone would like to do this; if no one steps forward, consider saying the following:

“Let’s close our meeting with a karakia.”

Kia whakairia te tapu

Kia wātea ai te ara

Kia turuki whakataha ai

Kia turuki whakataha ai

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e!

-

Restrictions are moved aside

So the pathway is clear

To return to everyday activities

To return to everyday activities

Unifed, connected and blessed.

A good written account of the meeting is important for recertification paperwork. The scribe should share their notes with everyone. To make the meeting more valuable, add the notes and links found during the meeting by the researcher.

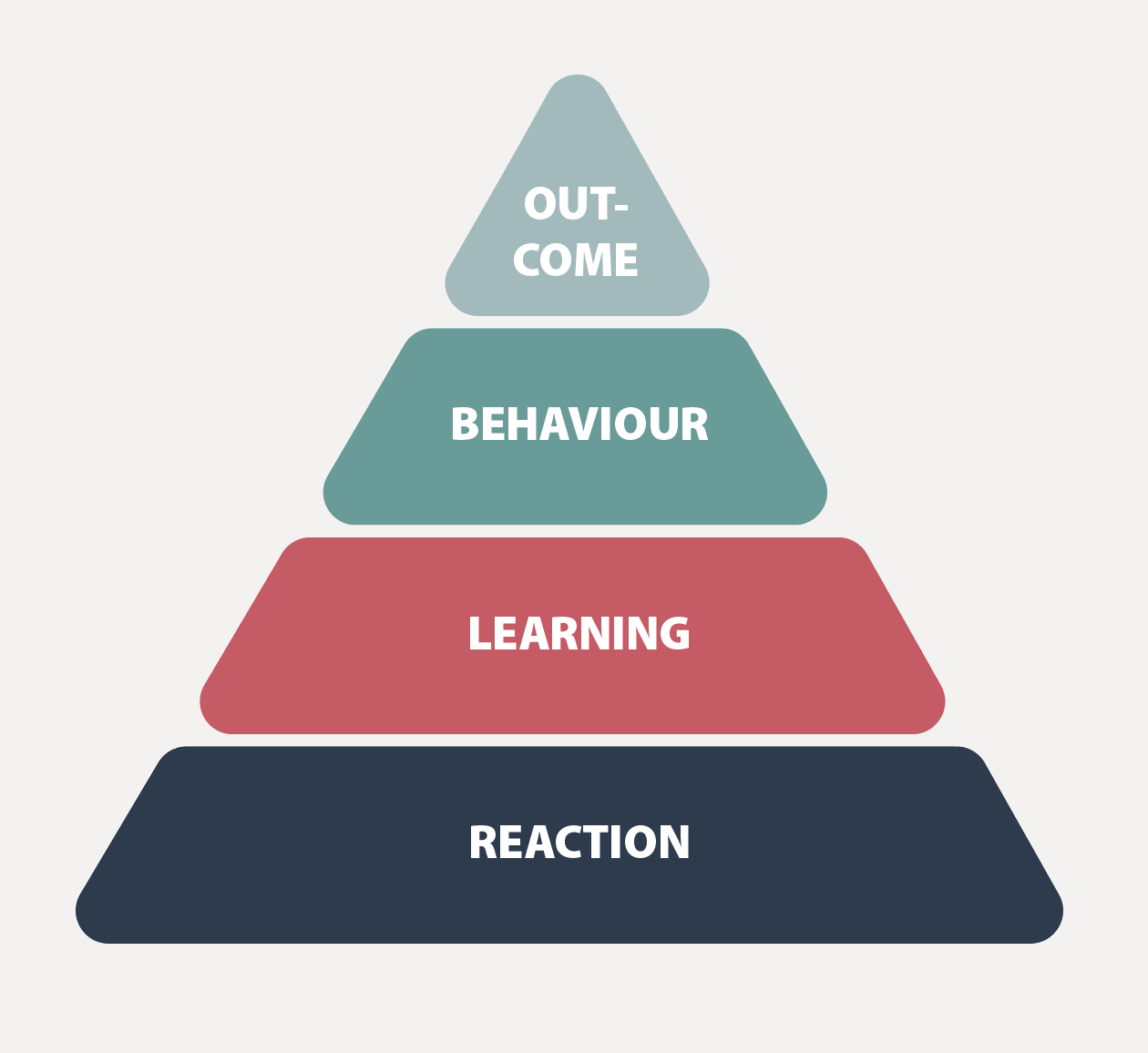

Being able to reflect on your own skills, attitudes and behaviours is essential for real improvement to occur. It enhances the educational value of peer groups to spend a short period of time reflecting on and recording what was gained.

Donald Kirkpatrick first described his four-level model for evaluating training programmes in 1959. It endures today and provides a great way to reflect on and enhance learning (Figure 2):3

Reaction – was your time spent well? Was the meeting engaging? What went well? What could be improved?

Learning – what three things did you learn about the topic or yourself that you did not know before? What surprised you?

Behaviour – have you changed your skills, attitudes, actions or behaviour as a result of this meeting?

Outcome – what impact has this meeting had on your care of patients? What outcomes have resulted?

Sharing these reflections at the start of the next meeting will reinforce the learning for everyone.

The group needs to reflect on how successful it is in meeting its purpose. If it meets only twice a year, a formal reflection and, if necessary, resetting of process and purpose every fourth meeting would be helpful.

A peer group should be a safe setting where variations in practice can be explored and discussed. Variation is normal – without it, we would never advance.

Different approaches are necessary for different contexts, people and communities, and it would be a very boring world if there was only one right way to do everything.

But imagine noticing the development of short-term memory loss in an older colleague in your peer group, who appears to have no insight into their condition. What would you do?

At the start, when setting up the group and discussing confidentiality, raise the possibility that there might be exceptions and how they will be dealt with.

Being able to reflect on your own skills, attitudes and behaviours is essential

Exceptions might include persistent unprofessional behaviour that puts patient safety at risk. No member of the group should object to creating a rule like this; if they did, I wouldn’t stay in that group!

The group could agree that any concerns about the health, or the skills, beliefs and actions of a member that might impact on patient safety will first be discussed directly and openly with the person concerned. This should allow for reflection and improvement, and it is a simple natural justice principle. A peer group where trust has developed between members is a great place to bring up issues that may be of concern and to discuss them.

If, after initial discussion, there is a persistent pattern of unprofessional behaviour, it is important to remember that patient safety comes first, and it is vital that concerns are raised outside the group. Initially, this may be with someone locally who might be responsible, the person’s employer or a PHO or DHB clinical leader. If that does not result in change, then concerns should be raised with the Pharmacy Council.

In a peer group setting, taking further action to protect patient safety could be decided on by consensus. Alternatively, any individual can, and should, raise their concerns externally, even if the group does not agree.

This is hard to do, but if this is discussed at the time the group forms, and laid out in the rules of engagement, it will be easier to apply.

Whenever you board a plane, you are advised that in the event of an emergency, you should put your own oxygen mask on before helping those around you.

Peer groups can be a fantastic way to ensure you have a support mechanism around you that helps you to stay safe and survive the pressures of working in the health system.

Future Pharmacy Today content will provide a framework for reflective peer group discussions. Topics will be aimed at progressing you towards culturally safe practice and at keeping you up to date with medicines, services and technology.

References

- Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;27(1):6–15.

- Tuckman BW, Jensen MAC. Stages of small-group development revisited. Group & Organization Studies 1977;2(4):419–27.

- Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, 3rd edition. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2008.