Academic pharmacist Nataly Martini highlights the importance of understanding non-Hodgkin lymphoma and pharmacists’ roles in managing this condition

Living with motor neurone disease

Living with motor neurone disease

June is Motor Neurone Disease Awareness Month. Pharmacist extraordinaire Dr Natalie Gauld (ONZM, DipPharm, MPharm, PhD, FPS) shares her experiences of being diagnosed with the disease

In February, people told me how great I looked – bronzed, relaxed and happy – after riding all over New Zealand the previous month.

Diagnosed in March 2022 with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), the most common variant of motor neurone disease (MND), I expect to lose the ability to drive, walk, speak, turn over in bed, scratch my head, feed and wash myself, sit up, swallow and breathe.

Think of Stephen Hawking with breathing equipment, a synthetic voice and a wheelchair, entirely dependent on others.

So while I can, I’ve maximised fun with friends and family, ridden the country’s trails on my three-wheeler, worked with great people on innovative projects, and, recently, been a panel member on medicines reclassification at a conference in Paris.

This is living with MND, making the most of my time.

In MND, the upper and/or lower motor neurons die.

Upper motor neurons go from the brain to and down the spinal cord.

Lower motor neurons go from the spinal cord to the muscles. Upper motor neuron damage involves spasticity, weakness and overactive reflexes and causes difficulty doing actions like walking or making hands work.

Lower motor neuron damage in MND causes muscle atrophy, muscle weakness and twitches (fasciculations).

In ALS, both lower and upper motor neurons degenerate, eventually instigating paralysis.

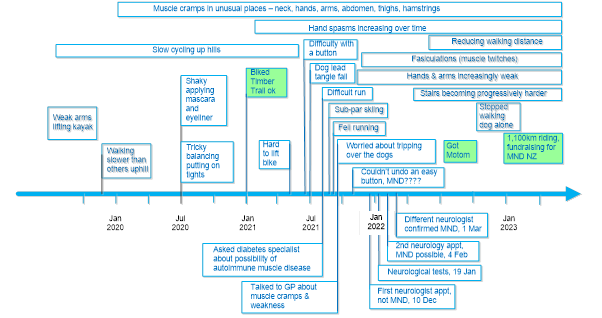

My symptoms and timeline are depicted in the diagram below.

Onset was typically insidious. I had shoulder weakness, slower walking and muscle cramps, the latter I attributed to my low-carb diet for diabetes.

My GP suggested a neurologist when I reported these symptoms: feeling like I was wearing concrete boots running and a fall when running.

The neurologist assessed reflexes, touch sensation and muscle strength.

Follow-up nerve conduction tests with electric shocks on the skin to measure nerve conduction, and electromyography with needles inserted into muscles to check electrical activity unpleasantly helped identify ALS.

Sixteen months from diagnosis, I walk slowly and carefully, finding stairs, slopes and standing harder. I worry about being knocked over.

I cannot jump, run, ski, get up from a squat, carry anything heavy or clean the shower (not the worst ability to lose).

My hands are weak. But I can still type, speak, walk, drive, and, importantly, laugh. My cognition is unaffected, although MND takes headspace.

MND is costly and time-consuming. Sufferers, and often their partners, reduce or stop work.

Home modifications take time and money, and highlight the challenges ahead.

Appointments with the occupational therapist, physiotherapist, respiratory service, neurologist, GP and massage therapist take time, as do exercises and voice banking.

Time is spent sourcing and learning to use equipment to navigate deteriorating physical capabilities eg, walking sticks and dictus splints (lifts the toe to avoid tripping), eating utensils, wheelchairs, hoists, eye gaze equipment and seats and beds that help lift a person.

Some equipment is unfunded. MND provides a compelling argument for income protection insurance.

Motor neurone disease occurs in one in 300 to 400 people in a lifetime, 90 per cent with no family link.

However, relatively few are affected currently as MND can progress fast, with some dying three to 12 months after diagnosis.

Stephen Hawking’s 55 years with MND (ALS variant) is an aberration. Only 10 per cent live more than five years after symptom onset with ALS; few last a decade.

Other variants include progressive bulbar palsy, affecting muscles of speech and swallowing first, with shorter life expectancy than ALS; progressive muscular atrophy with longer life expectancy; and primary lateral sclerosis affecting only upper motor neurons, with good life expectancy.

Some have frontotemporal dementia, with cognitive changes.

I appear to be in the top 10 per cent for longevity, few have my capability 16 months from diagnosis and four years from symptom onset, but I am progressing.

There is no cure, but studies suggest riluzole provides a survival benefit of six months or more.1 Regular liver function tests are required.

Considerable research activity, including viral vectors for gene editing, provides hope for a cure or disease modifier.

New Zealand’s Centre for Brain Research is active in MND research, including holding an MND patient registry funded by Motor Neurone Disease New Zealand and brain tissue from MND sufferers. MND NZ funded the first patient treatment trial recently.

Given immobility and carer burden, try to avoid repeats – suggest patients arrange their prescription early where possible to help avoid owes. Delivery can help. Hand impairment can affect breaking tablets, pulling apart sticky taped boxes and opening some containers. Some have pain; an MND sufferer was upset when he perceived the pharmacist mistrusted him regarding his opioid use. Encourage people to talk to MND NZ for support of patients, carers and family.

Some people understandably don’t know what to say to someone with a devastating disease like MND.

Like others, I appreciate a simple email “how are you doing?”, or “sorry to hear about your diagnosis, thinking of you”.

Around Global MND Awareness Day – 20 June – help support MND patients and research to stop this cruel disease by doing the Ice Bucket Challenge or donating to MND NZ at mnd-new-zealand-fundraise.raisely.com/natalie-gauld (note this is not for me). If you donate, email me so I can thank you personally (natalie@nataliegauld.com).